Reading Time: 10 minutes

Summary:

- Some early theologians, like Origen, saw the rapture as a purely spiritual event

- Rufinus viewed biblical references to a rapture as a statement about the nature of the afterlife

- Other early theologians, like Augustine and Chrysostom, did associate a physical rapture event with the Final Judgement

- Many modern depictions of the rapture in pop culture come from a theology developed by John Darby in the 19th century

What do we Mean by “Rapture”?

The Final Judgement has become a staple of Christianity’s interaction with pop culture. Whether through cinematic depictions of apocalyptic natural disasters, or literary references to the Four Horsemen, many today, whether Christian or not, have developed some sort of idea about what the last days will look like.

Chief among those ideas is some working understanding of a rapture of believers, where Christians around the world will be taken up into heaven prior to the unleashing of the cataclysmic events that most associate with the end times. Images of empty piles of clothes and cars whose drivers had suddenly disappeared have been a part of the popular understanding of the rapture for decades, and many do not question whether such an event plays out like this. But how did we get here? Where did these popular understandings of the rapture come from, and how do they compare to what the church historically taught regarding the rapture and Final Judgement?

Let’s begin by examining the origin of the term, “rapture,” itself. Like much of our modern vocabulary, the English word is derived from a Latin word used in the Latin translation of the Bible, called the Vulgate. The word in question is mentioned in 1 Thessalonians 4:16-17:

16 For the Lord himself will come down from heaven, with a loud command, with the voice of the archangel and with the trumpet call of God, and the dead in Christ will rise first. 17 After that, we who are still alive and are left will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air. And so we will be with the Lord forever. (NIV)

The Latin word, rapio, is used in verse 17 when Paul says “will be caught up”, and it is from this association with being “caught up” or “carried off” that we get the word, rapture. Long before this word was ubiquitous in modern culture, however, the early church fathers wrestled with the concept of the rapture (if they didn’t necessarily call it by that word) by examining the above-mentioned verse and other scriptures relating to the end times.

A Spiritual Rapture

Origen, a 3rd century theologian and “Church Father”, looked at 1 Thessalonians 4:17 in a largely spiritual way, defining the dead and the living not based on any sort of physical condition, but on their relationship to Christ. “Those who have been perfected,” he claimed, “are alive in Christ,” while the dead in Christ were those who were still inclined to become overpowered by their human nature, and so, in his view, had not completed their union with Christ. From this perspective, Origen sees Paul’s idea of being “caught up” as a sort of spiritual resurrection. “Those whom we said to be dead have special need of the resurrection,” says Origen of this passage of Scripture.¹ So, in Origen’s view, the rapture was not so much a physical carrying off, but a spiritual resurrection, needed most by those who are furthest from Christ.

Rufinus of Aquileia, a 4th century theologian, similarly attributed a spiritual significance to the idea of the rapture, although he was more apt to see it as a physical event as well. “And do not marvel that the flesh of the saints is to be changed,” wrote Rufinus, “into such a glorious condition at the resurrection as to be caught up to meet God, suspended in the clouds and borne in the air” (emphasis added).² Rufus and Origen both saw a spiritual significance to the rapture, describing it as the final step in complete union with Christ. Rufinus, however, sees this event as being a part of the final physical resurrection, where the physical bodies of believers are exchanged for a more heavenly form. In this context, though, Rufus is not speaking of the Last Judgement necessarily, but about the final fate of Christian souls. To Rufinus, this physical carrying off is not inherently tied to the Great Tribulation mentioned in Revelation, but simply represents what ultimately awaits believers in Heaven. He does not state that this carrying off will be a single event that affects all believers worldwide. Instead, the rapture to Rufus is more like a statement about the nature of the afterlife, one where physical forms are replaced by heavenly bodies and believers commune with Christ for eternity.

These two theologians, Rufinus and Origen, primarily focused on the nature of the rapture’s significance. In other words, they were concerned largely with what it would mean for believers once the rapture, as they understood it, had reached its end. Contrast that approach with the likes of John Chrysostom, who was instead far more interested in the nature of the rapture’s occurrence.

A Physical Rapture

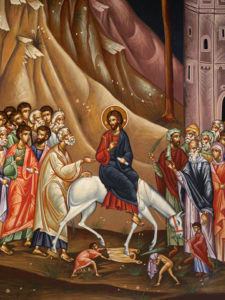

“If He is about to descend, on what account shall we be caught up?” Chrysostom muses. “For the sake of honor. For when a king drives into a city, those who are in honor go out to meet him; but the condemned await the judge within…as He descends, we go forth to meet Him…”³

Chrysostom, a 4th century church father famed for his eloquent public speaking, answers his own question by employing an analogy about a king entering a city, and how his subjects come out to meet him before he arrives at the gates, preparing a way for his triumphant entry. This imagery conjures up more modern ideas of the rapture as seen in pop culture. Chrysostom associates being caught up (note his use of the term, like Origen and Rufinus) with the final judgement, as Christ is envisioned as a king returning to his city to judge the righteous (those “who are in honor”) and the condemned. In his telling of events, the rapture occurs before the coming of Christ, as in his analogy the citizens ride out to meet the king before he enters the city, and those who are not “in honor” remain in the city until the king comes to judge them. This certainly seems to imply that a real event, where believers are carried off from this world before Christ returns, is going to occur, according to Chrysostom. Augustine similarly implied that such a thing would happen, stating that a “resurrection shall take place in the twinkling of an eye,”⁴ bringing to mind the instantaneous disappearance of believers around the world that is often seen in cinematic depictions of the rapture.

John Darby and the Modern Rapture

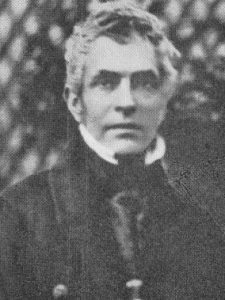

Though Chrysostom and Augustine laid a rough framework that vaguely resembles modern ideas of the rapture, the credit for fleshing those ideas out and establishing a firm understanding of the rapture as a global event that precedes the Second Coming of Christ goes to John Darby. In the 19th Century, Darby championed a novel way (for the time) of reading Scripture, which was strictly literal, and focused much of his attention on the end times prophecies in the book of Revelation. It was through this interpretive perspective that Darby concretely separated the rapture and the Second Coming as two distinct events, largely based on the reading of Revelation 20:1-6

1 Then I saw an angel descending from heaven, holding in his hand the key to the abyss and a huge chain. 2 He seized the dragon—the ancient serpent, who is the devil and Satan—and tied him up for a thousand years. 3 The angel then threw him into the abyss and locked and sealed it so that he could not deceive the nations until the one thousand years were finished. (After these things he must be released for a brief period of time.)

4 Then I saw thrones and seated on them were those who had been given authority to judge. I also saw the souls of those who had been beheaded because of the testimony about Jesus and because of the word of God. These had not worshiped the beast or his image and had refused to receive his mark on their forehead or hand. They came to life and reigned with Christ for a thousand years. 5 (The rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were finished.) This is the first resurrection. 6 Blessed and holy is the one who takes part in the first resurrection. The second death has no power over them, but they will be priests of God and of Christ, and they will reign with him for a thousand years.

Darby saw the thousand-year reign mentioned in Revelation 20 as a literal 1,000 years, and as a distinct era of history which was to be marked at its beginning by the Second Coming. That Second Coming, however, was to be preceded by a rapture, where Christ would assemble all Christians, living and dead, with Him in heaven before returning to begin this millennial reign with them. In between these two events (the rapture and the Second Coming), all the apocalyptic events of Revelation would occur, known as the Great Tribulation.

Darby’s specific view of the rapture and Second Coming garnered the name, dispensational premillennialism, so named for Darby’s desire to divide the world’s history into distinct eras (or dispensations), and for the fact that Christ’s Second Coming would be occurring before His millennial reign (thus, premillennialism).

The Rapture in Pop Culture

This view of the rapture, dispensational premillennialism, has given rise to much of what we see in pop culture with regards to the rapture and accompanying apocalypse, due to its wealth of content which translates well into books and movies. The Left Behind series, for example (both the books and films), drew upon dispensational premillennialism’s history of literal interpretation to create a story built around the premise of the literal fulfillment of all of Revelation’s prophecies, including a global rapture event that preceded the Second Coming of Christ.

The rapture is not exclusive to premillennialist views, however, as the term, premillennial, largely denotes the timeframe of Christ’s return, not necessarily the nature of any sort of rapture event. Postmillennialism, for example, claims that Christ will return after a thousand-year period of blessedness and prosperity on earth. Amillennialism, on the other hand, views the thousand years mentioned in Revelation 20 as largely symbolic, or as a metaphor, where Christ’s reign is over a spiritual kingdom on earth, rather than a literal one.

A version of the rapture could conceivably fit into any millennial framework. Origen and Rufinus’ claim that the carrying off mentioned by Paul in 2 Thessalonians is largely a spiritual experience pairs well with the spiritual approach to scripture offered by amillennialism. Postmillennialism claims that Christ’s coming is accompanied by his judgement on the wicked (as opposed to dispensational premillennialism, which separates the two events), which seems to be what Chrysostom is implying in his understanding of the rapture, and so the two are compatible.

The version of the rapture we see in premillennialism and espoused by John Darby (which also is compatible with what Chrysostom claims) is by far the most recognized in pop culture of the three, although in terms of its acceptance within the church, there is a relatively even split amongst the millennial views. Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches for the most part reject the idea of a pre-tribulation rapture event (dispensational premillennialism view), and opt to interpret the rapture instead as Rufus and Origen did.

Denominations more apt to interpret the scriptures through a literal lens, in the way that John Darby did, are more likely to accept the idea of a global rapture event preceding Christ’s Second Coming. Thus is this view found in Protestant churches more than anywhere else. The Pentecostal denomination accepts this version of the rapture as truth, and many Southern Baptist laypeople hold this view as well, though the denomination does not officially claim it as a central tenant. Protestant denominations such as Presbyterians, Methodists, and Anglicans, to name a few, reject Darby’s view and instead hold to Origen and Rufinus’ view.

So, whether a church views the rapture as a spiritual event, or a physical one, and no matter the timeline, there is precedent in church history for such belief. While the idea that Darby championed of a global event that marks the beginning of the Great Tribulation is by far the most familiar view among those outside of the church, it is by no means the only option for Christians to adhere to regarding the rapture and Second Coming. Church fathers throughout history have examined the particular scriptures that deal with the rapio, the carrying off, and their conclusions offer up a host of ideas that any Christian would be in good company to hold.

What view have you heard about most often? Let us know in the comments.

About the Author

Will Libby holds an undergraduate degree in Philosophy of Religion from Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee, and currently works as the Director of Youth Ministries at a church in Norfolk, Virginia. He is a musician and poet, and is passionate about the relationship between theology and the arts, a subject he hopes one to study as a part of his Master’s degree pursuit.

Footnotes

¹ From Commentary on the Gospel According to John, Book 20

² From Commentary on the Apostles’ Creed, 46

³ From Homily on 1 Thessalonians, VIII

⁴ From City of God, 20.20