Reading Time: 15 minutes

Summary

- How have Christians thought about suicide over the centuries?

- We explore:

- Personal story

- A common misinterpretation

- Biblical foundations for suicide discussions

- What past theologians have to say on suicide

- Closing personal remarks

Introduction

I had a time, and a plan. Things had gone as bad as they could, for about as long as they could. Finally, rationally (all too rationally), I had arrived at the conclusion to end my life. There was a coolness to the calculation, not like the occasional seasons of sadness I’d experienced before. This plan was made after years of having my reasons to stay alive chipped away. It was, fortunately, not the last choice I would make.

I write this now, not because I think I can answer the question as to why all people commit suicide. I certainly don’t do it for attention. I don’t know whether there is a “spiritual practice” or “mystical healing” which can free every person from suicidal tendencies.

I write this, because it was the theology and history of the church which helped me begin that journey back to a place of acceptance and peace. This is important, because it seems that this engagement of the church with people considering suicide is missing. Like most people stuck in a place where self-murder becomes a real and viable choice, I knew the emergency hotline numbers. I had gone to therapy sessions, meant to snap me out of a mental state. These lifestyle lessons would be vital for maintaining my mental equilibrium. But therapy and phone numbers were not enough to tackle my real problem. I recall walking out of a therapy session and acidly joking, “Oh good, now I know how to breathe calmly and drink tea while thinking of killing myself.” In the mix of life, work, and the long sadness, I was missing something. I was missing the church.

This writing is for those who have had similar thoughts, and a similar need to get some spiritual engagement on the subject of suicide. The church is, after all, very far from empty on this topic. It is also for Christians who would like to seriously care for those among them who struggle with the wish to end their lives. Together, and by the grace of God, perhaps we can reconnect the church, society, and ordinary people to the theology of the church, which has always preached life, at all times, and in all places.

The Problem

Let us be clear that no tradition or denomination of the Church is an advocate of suicide.[1] And yet, the Church, particularly churches with a strong sense of predestination, do not seem to see how elements of theology can create a case for suicide. The Church always calls for life; and yet our beliefs, when poorly communicated and misunderstood, can very easily be understood as a call to die.

Drawing from my own experiences, from the experiences of theologians such as St. Augustine, and from the experiences of my friends, the basic tenets of this warped theology, not of life but of death, goes as such:

- All humanity is fallen. We can understand this as general sort of guilt which is part of being human. But we can also feel this fallenness in a very personal and intimate way. This “guilt” and “fallen-ness” I once described as a feeling both strong and as common as putting on shoes in the morning. Others have described this feeling like walking around while wearing a coat made of lead. It is a personal sense of brokenness which seems as big as the world; this is right, because it is as big as the sufferer’s view of the world. In his seminal work, “Orthodoxy,” G.K. Chesterton has this to say about suicide: “A suicide is a man who cares so little for anything outside him, that he wants to see the last of everything… spiritually, he destroys the universe.” And this is very true: a suicide is drawn into themself by some deep wound. The hurt is so intimate, a suicidal person would nearly destroy the whole universe just to be rid of it; from their spiritual and psychological viewpoint, a suicide does just that.

- God’s grace can take away this sin, but fallen human nature immediately adds more sins through new failures and bad habits. This makes the taking away of sin functionally meaningless. There was a very cruel experiment in the 1960’s, involving putting dogs in a room with an electric floor. Half of the floor would be electrified, the other half not. Dogs that had been conditioned to accept the shock as a thing impossible to avoid would simply lay down on the painful floor, whereas dogs that had not been conditioned into “learned helplessness” would jump to safety. It is dangerously easy for the church to teach about sin and forgiveness in a way that conditions believers into a kind of learned helplessness. We are shocked by our sins, but having begged Christ for months, and likely years, for rescue and relief, we are still left with our sinfulness. The floor is shocking.

The first response to this logic is, of course, that the grace of God is sufficient to cover our sins. However, when this Grace fails to cause a change in our habits, that Grace becomes functionally meaningless. “Faith without works is dead.” (James 2:14) When sinfulness is combined with habits, addictions, and predispositions, things get even worse. When a drunk turns to alcohol to deal with their own sense of unworthiness, this drunk must now deal with the double problem of their habitual unworthiness, and habitual drunkenness. The two problems feed off of each other. As the famous theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer in his book “The Cost of Discipleship,” said of this situation, God’s Grace becomes cheap. - A life lived constantly aware of sin and with only meaningless grace is not worth living. This stage in the logic of the suicidal Christian can last for years, in fact for a full lifetime. Sometimes God helps people in such a condition with some sort of saving revelation: a mystical vision, or some bolt of true grace and theology which offers freedom as with St. Augustine.[2] However, these exceptions do not form the rule. For most, this is a period of deterioration, of loss, of the slow grinding down of all evidence that amazing Grace could come to one as wretched as me.

- Thus, the only method to freedom from sin, is to kill the sinner, and so the self.

This logic can reflect different ideologies and positions; for example “sin” might be replaced with an idea of “wrongness,” “imperfection,” or “incompleteness.” Overall, the vital component of this logic is a sense that we, as humans, are not enough. There is an ideal of holiness and perfection which we were meant to meet, but have failed to do so. This impurity is passed on through our actions, and is greater than the good which we produce.

The difficulty to counter this rationale, theologically, is that it is in a sense half right. We as fallen humans do live a broken life. To take the example of Anselm of Canterbury and his satisfaction theory of atonement, to turn our eyes away from God for one moment is to be guilty of an infinite failure, which can never be made up by our own actions. As people who turn our eyes away from God on a daily basis, we certainly are right to feel a sense of guilt. To borrow the phrase of Jonathan Edwards, we are “sinners in the hands of an angry God.” For those formed in the Christian tradition, this cocktail of personal guilt and the great holiness of God can be crushing.

Often the answer provided by friends and mentors to this struggle is a push towards action: follow Christ, push forward, exercise, do something (anything) productive. However, a change in our habits or routines is not enough to fix suicidal thoughts based on this deep, intimate kind of hurt. This is because the choice to end life is an extremely intimate choice. This is perhaps especially true when the decision is based on a broken theology. When lay people or even pastors say things like “I was depressed once, and came out of it. You can as well by prayer/Grace/God’s power,” it can do more harm than good. It is right to say that God’s grace can forgive sin; but when said by someone unwilling to meet us in that place of hurt, the words lose all their power. At its worst, this surface care which does not go into the deeper issues of depressions can lead to things like believers with severe mental or physical conditions refusing medication in order to rely only on supernatural, miraculous support (which is a kind of testing of God). It can also lead to church members defining spiritual health by how happy a person is, which is a very faulty and fluctuating scale.

We might think the answer is to take each person on a case-by-case basis, and to try to find out the needs and the path to recovery of each individual. It sounds correct, but anyone who really suffers with depression knows how hollow that can sound. After a celebrity suicide, the news stations broadcast the emergency suicide help hotline number. Admirable as this action can be, the effect is almost inevitably canned. These statements posture toward empathy, as a kind of covering of moral bases, and refuse to actually engage the problem.

We must engage suicide. But we must engage carefully. The Church throughout time has left some help on how to do just that, starting with the Bible.

Biblical Foundations

There are seven suicides in the Bible (taken from the NIV):

- Hurriedly, (Abimelech) called to his armor-bearer, “Draw your sword and kill me, so that they can’t say, ‘A woman killed him.'” So his servant ran him through, and he died. (Judges 9:54).

- Samson said, “Let me die with the Philistines!” Then he pushed with all his might, and down came the temple on the rulers and all the people in it. Thus he killed many more when he died than while he lived. (Judges 16:30).

- But his armor-bearer was terrified and would not do it; so Saul took his own sword and fell on it. (1 Sam. 31:4).

- When the armor-bearer saw that Saul was dead, he too fell on his sword and died with him. (1 Sam 31:5).

- When Ahithophel saw that his advice had not been followed, he saddled his donkey and set out for his house in his hometown. He put his house in order and then hanged himself. (2 Sam. 17:23).

- When Zimri saw that the city was taken, he went into the citadel of the royal palace and set the palace on fire around him. So he died, (1 Kings 16:18).

- So Judas threw the money into the temple and left. Then he went away and hanged himself. (Matt. 27:5).

Death of King Saul by Elie Marcuse, 1848

The traditional reading of these suicides is as a kind of judgment or punishment from God. This reading is to some degree very sound. For example, there is definitely a sense of punishment in the stories of Abimelech or Zimri. Abimelech’s death is very much taken as the death of an evil man, who has by the action of murdering his seventy brothers reaped the consequences of his own ego. His last words are tinged with a kind of misogyny which makes it hard to mourn him much. We do not cry over the death of a mass-murderer.

Things get more complex when we consider Saul or Ahitophel. Ahitophel was a counselor to Absalom, David’s son. King David was not a perfect king (anyone who has engaged in a political election knows all too well that political maneuverings are rarely a case of black and white judgements). If we understand Ahitophel’s suicide in the Bible as a kind of punishment, we have to struggle with the fact that Ahitophel’s greatest sin was backing the wrong horse, and not a moral fault. Reading closely, we see an old man, pursued by the king, his honor lost, his voice unheard. A perfect manager, he returns home, methodically puts his affairs in order, and hangs himself.

Then, take the most ambiguous of Old Testament suicides: Saul’s armor-bearer. We may say that the choice to fall upon his own sword at the sight of Saul was an act of sin. We may not say that the armour-bearer’s suicide was a kind of judgment for actions he had taken in his life. If anything, we see that his suicide was done out of a kind of love for his master, or at least fear for his master’s enemies.

To read the suicides in the Bible only as the judgement of God is too clean of an answer. It comes back to that idea that redemption can be too little and too “cheap” to cover our sin. It seems to me that despair is a much better way to think about the suicides of the Bible. Saul sees no exit but death. Samson could see no good end, but in the end of his enemies. Each act of suicide, as an act of despair, bans any chance for redemption.

We can feel this ripping away of the chance for redemption at full strength in the the only New Testament case of suicide: Judas. Could Judas have been forgiven, if he had not killed himself? With the Old Testament examples, we can see that if they had not died by their own hands, they would have died by the hands of their enemies. But the only one who might have revenge on Judas was Jesus Christ; and Jesus came to redeem all people. We are left wondering about the forgiveness of Judas, as a kind of ache. Judas’ suicide takes away from us any chance of seeing such potential reconciliation.

Church Tradition

The traditions and history of the church also speaks about suicide, and can provide some help on the way away from that fatal, final choice. For the person who is trapped in the warped theology presented above, and believe that suicide is a kind of altruistic act, the early fathers of the Church are worth listening to. This is because these early theological voices in the church do point out that this view of killing oneself is not entirely wrong. There can be something redemptive, even holy, in the conscious decision to end my life.

The right way to make that last choice, according to the fathers, was martyrdom. Tertullian, one early church father, writes to Christians in prison waiting to be executed for their faith. To encourage these soon-to-be martyrs, Tertullian cites the famous stories of Lucretia, Dido, and Cleopatra. Similarly, John Chrysostom and Ambrose of Milan both applauded Saint Pelagia, who threw herself off the roof of a house to avoid capture by Roman soldiers. The choice to end life is only a righteous choice, when it is centered not on ourself, but focused outwardly. In the ancient, pre-Christian stories of Lucretia, Dido, and Cleopatra, suicide is the protection of something virtuous like chastity.

What we find here is that suicide and martyrdom are two acts, which while looking similar, are utterly and intensely in opposition to one another. Suicidal thoughts always turn us inward upon ourselves. We grope around in the darkness of our own psyches. Others such as family and friends tell us that our view of life is distorted. They do not see that the person who has come to the brink of suicide has been lost groping in darkness for so very long, lost within darkest parts of their own shadows.

Martyrdom is the opposite of this. It is perpetually looking outward. For the true martyr, even the glory or being a martyr has been eliminated; they have something far better in their sight. They have no time to worry about finding themselves; they are too busy finding their way into the heavens. The truth is that both suicide and martyrdom are a kind of falling into an eternity: the suicide falls forever into an inner darkness, the martyr falls forever into the light of God.

By medieval times, the church had developed this strong distinction between suicide and martyrdom. Perhaps the most vivid exploration of this is in the first part of Dante’s Divine Comedy, the Inferno.

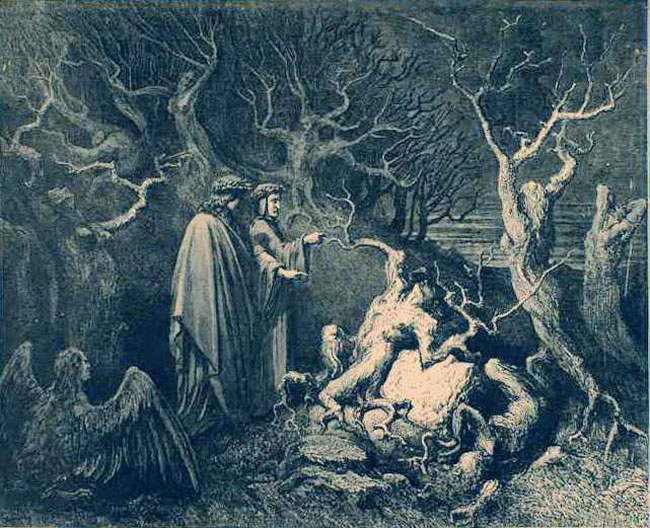

“Dante and Virgil before Pier della Vigna” by Gustave Dore, 1890

In Inferno, souls who have ended their own lives are left, bodiless, to be cast into a forest, where they grow into trees constantly broken and harrassed by harpies. After judgement day, these souls will return for their bodies; but because it is not right for people to have back what they have thrown away, these souls will have their bodies hang from the branches of their trees. It’s important to note that this fate is not for every suicide in Dante’s conception. The Greek politician Cato, who killed himself rather than live under Julius Caesar’s rise to becoming emperor, is placed within Purgatory with all hope and promise to reach heaven eventually.

Suicide for Dante, and the medieval world in general, was seen as a kind of ultimate rejection of God. Thomas Aquinas, one of the most celebrated medieval theologians, notes that life is a quality of God, and so living (or “being”) in itself is a good. Suicide is to take the good which God gives us and say “no thanks.” Your life is valuable in itself, without you trying to earn any goodness. That goodness needs to be nurtured, and allowed to grow; but that goodness, paired with the Grace of God, can never be turned into something so evil that it deserves the end of life.

The value of every life is something that defines Christianity. It was fully explored during the medieval period, but has since been modified to fit each following period in history. For example, G.K. Chesterton, writing during the early 20th century, talks about suicide as a kind of cowardice, and a “refusal to take an interest in existence; the refusal to take the oath of loyalty to life.” Despite these differences, or maybe flowing through these alternatives, the central message of church theologians remains the same: life is valuable, blessed with the image of God (imago Dei), and only to be cast aside with the hopes of throwing our lives into something more valuable. We do not create good by destroying ourselves.

Conclusion

This reflection on suicide is very obviously imperfect. It was not designed to be perfect. It is merely, in the end, a survivor’s memoir. In it, you find my story, as well as the logic and research which helped keep me alive. It is what worked for me, on the long road back to life, full of backsliding and victories.

If you know someone who is suicidal, cultivate compassion. This does not mean to accept or excuse the inherently selfish ideas and actions of your friends and family who talk about ending their lives. It does mean doing the hard, awkward, and complex work of helping them try to find their way out of that labyrinth-like darkness.

If you are suicidal, or sometimes find yourself in that darkness, I can only offer you the truth that it can get better. I do not know your story, I do not know what you need to find freedom. But if I can offer any advice, it would be to search for what you need to start moving forward again. If it’s an answer to some theological puzzle, search deeply for the Truth. If it is some deep emotional need that is not met, make the purpose of your life the search for that Love. Do not give up. Because if you can survive that dungeon within you, you will come out so strong, and so brave. And I should be very glad to meet you, one day. Because you will have wings which can take you to places of gratitude and love not comprehensible by most. The larval stage is pretty rough though. I can also add that, those dungeons and dark places in you never really leave. You will find your way back to them at times. The dungeon and darkness is a part of you. But when you are not held captive in the dungeon, when you can go freely to and from it, you will find that even the dark places have their own inner light, and even the dungeons, as part of you, are not without their own savage beauty.

Comment below if you know someone who struggled with suicidal thoughts before.

Footnotes

[1] The only, barest exception to this ban may be in the face of severe, chronic, and life-ending illness, and the passing is assisted by a doctor or other professional. This sort of ending of life is an ethical issue, amongst churches and general society, beyond our discussion today. All other suicides are seen by the church in a significantly negative light.

[2] Here, I am mainly referring to St. Augustine’s conversion in his Confessions; however, it is worth noting that St. Augustine also wrote extensively on the topic of suicide. I would particularly recommend his City of God, in book 1, chapters 16-20.

Biography

Evan is a published poet and author living in Moscow, Russia. He holds a Masters in Theological Studies from Duke Divinity School, and a Bachelors in Theology from Whitworth University. He has worked as a youth pastor, instructor in theology and church history, and English teacher. He hopes to gain his PhD in the field of Theological Aesthetics, particularly focusing on medieval and early modern literature.